Midnight sun at Nordkapp, Norway, by Yan Zhang via WikiPedia (GFDL license)

At northmost Norway during a Midnight Sun you could stand at Cinderella’s magic hour and have your eyes scorched by a relentless track of light on sea. No matter where you moved the path would aim at you, you. Edvard Munch lived below the Arctic Circle in Norway yet painted this ramrod dazzle more than once.

“My fear of life is necessary to me, as is my illness,” he once wrote. “Without anxiety and illness, I am a ship without a rudder…” via smithsonianmag.org

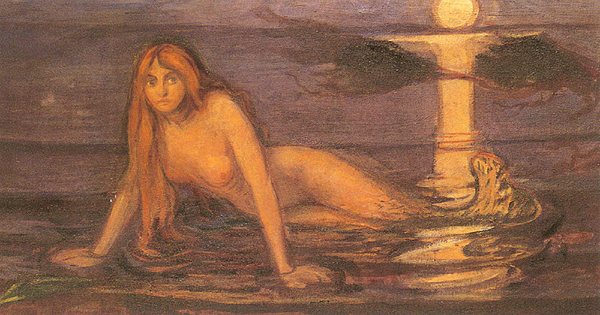

In The Voice and in Lady From the Sea you can deduce where the artist imagined himself in relation to his subjects. The mermaid’s stare looks warily at something off to the right of the painter, for the blaze of sun points to him.

Summer Night’s Dream (The Voice), by Edvard Munch, 1893 via Maher Art Gallery

Lady From the Sea by Edvard Munch, 1896 via sisterwolf.tumbler.com

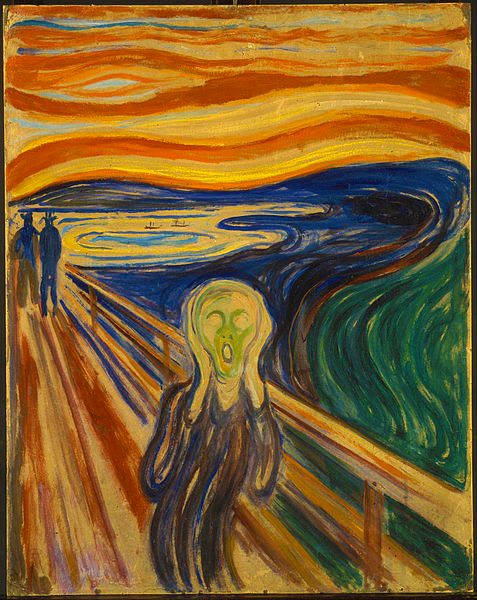

Munch also painted this icon of angst and overload:

The Scream of Nature by Edvard Munch, pastel on cardboard, 1895 (his copy of his 1893 painting) via 2Space

Munch leaves us a body of work thick with isolation, threat, sexual torque, sickrooms and deathbeds. Born in 1863, the painter lived when artists had begun distilling emotions in their subject matter. It suited him and he pumped outsized emotions for fuel.

I was working on this piece when the Boston bombs exploded and I couldn’t stomach Edvard Munch for a spell. There’s a yuck factor in his work, something you’re uneasy to witness. Yet when you step back you must feel compassion for Munch’s eighty haunted years.

Yes the hounds of hell sat loyally at his feet where he fed and fondled them. Not a recommended emotional state but a true-to-life one. Many of us slip into the howling from time to time.

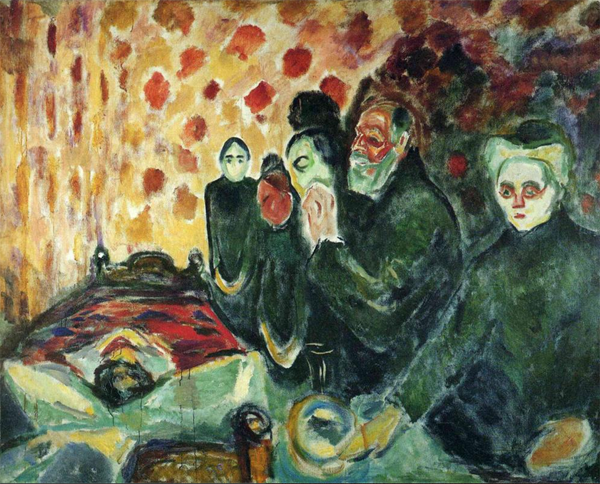

Notice how eerily the same are these two renditions of the same scene, painted 20 years apart:

By the Deathbed (Fever) by Edvard Munch, 1893 via WikiPaintings

By the Deathbed (Fever) I by Edvard Munch, 1915 via WikiPaintings

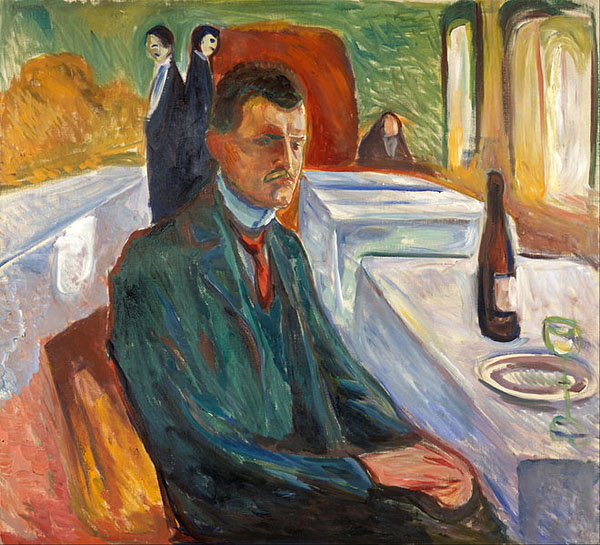

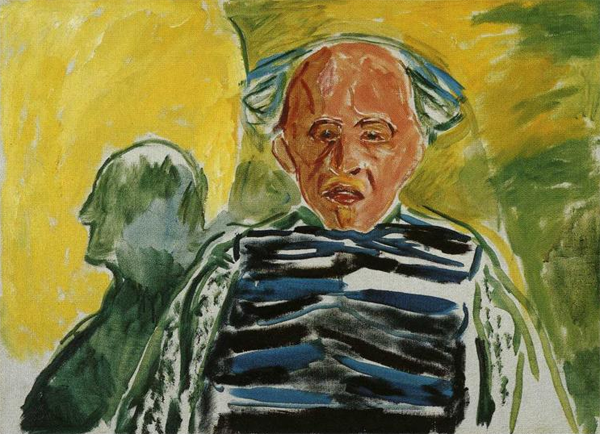

Two Steppenwolf views — Edvard Munch paints himself:

Self-portrait with bottle of wine by Edvard Munch, 1906 via wikipeedia

Self-Portrait with Striped Pullover by Edvard Munch, 1944 via WikiPaintings

An eighty-year-old painter feeling self-disgust? A tragedy.

________________________________________________

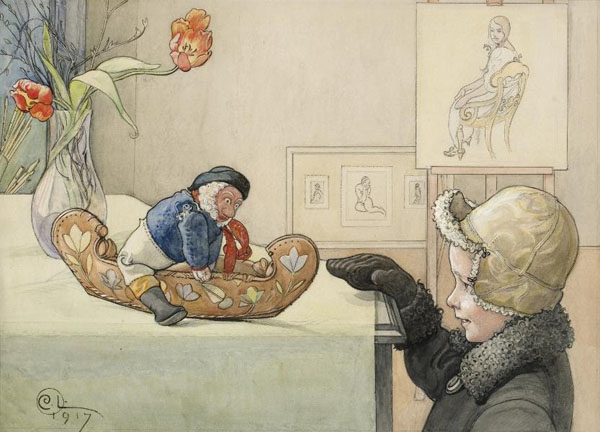

Den lustiga gubben by Carl Larsson, 1917 via A Polar Bear’s Tale

I look at this painting by Carl Larsson and believe in this moment. That a child and two toys met and that the child’s delight had a bright imaginative intensity. The kind grownups can only remember remembering. That emotional state is as real as any adolescent’s crush or merger mogul’s furrowed focus.

We tend to think of a child’s or teen’s emotions as less valid than an adult’s. And we sometimes think that Munch’s world is realer than Larsson’s.

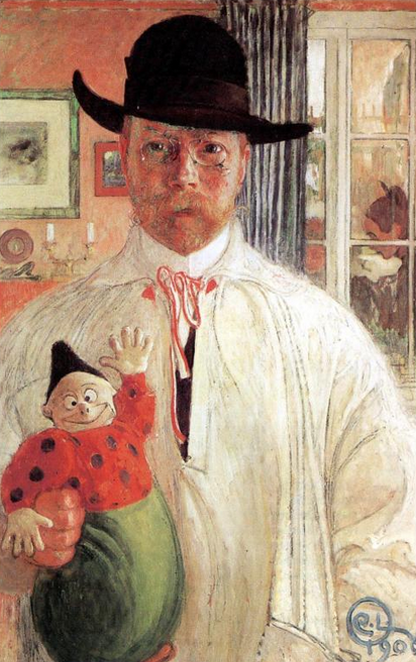

The Swede Carl Larsson is at the extreme oppposite emotional pole from Munch. Born ten years before, dead at a much younger age — he portrayed the world with an amused and loving eye. He painted people, pets, vigorous plants, wacky dolls, the colorful rooms of the house he and his wife decorated with exuberance . He seems blind to dark corners. Compare his tongue-in-cheek Self-Recognition with Munch’s harrowing self-portraits.

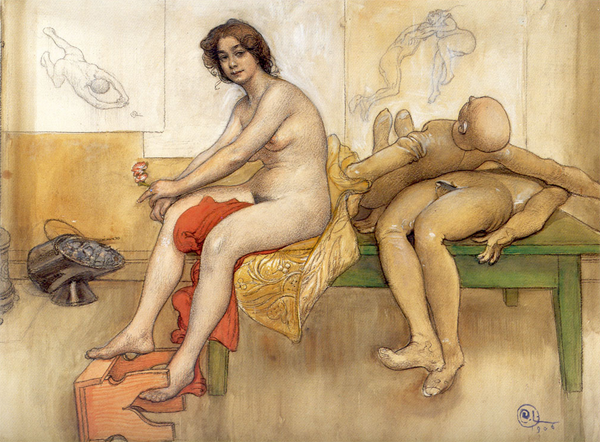

Self-Recognition by Carl Larsson, 1906 via WikiPaintings

Books of Carl Larsson paintings were big in my home. My mother regaled me with idyllic stories of life in a big vibrant family in a neighborhood crammed with children.. Fairytale, right? I’d see the Larsson images, soak up my mother’s tales and wonder what was wrong with me. I wasn’t happy. I know now that I lived in a beautiful home that was empty of people. The magic had been in having enough personalities that kept caroming off each other.

I disdained Larsson for a while. No dark corners? Ha! Yet today I pair him with Munch because there may just be pockets where neurosis doesn’t rule. And because we have no trouble believing in Munch’s anguish but figure Larsson’s vision of wholesomeness must be schlock. And yet how many of history’s painters could convincingly convey happiness?

Woman Lying on a Bench by Carl Larsson, 1913 via fineartamerica

I think that Larsson captures the easy happiness of the not-rich-not-poor-not-crazy in a time before Toys ‘R’ Us, newscasts, freeway interchanges and ads in every medium. Simple pleasures far from from the jangling pressures of our day.

Christmas Morning by Carl Larsson, 1894 via Hammcrafted

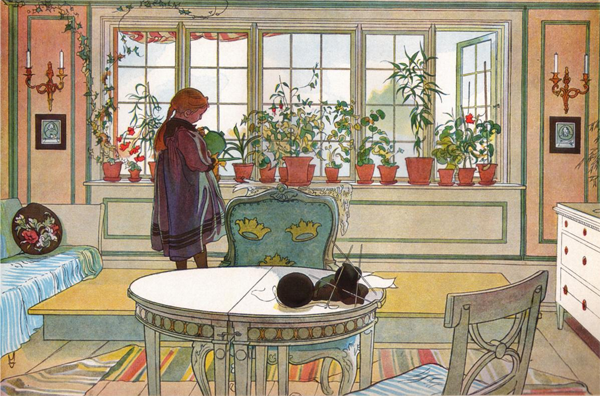

Flowers on the Windowsill by Carl Larsson, 1894 via WikiPaintings

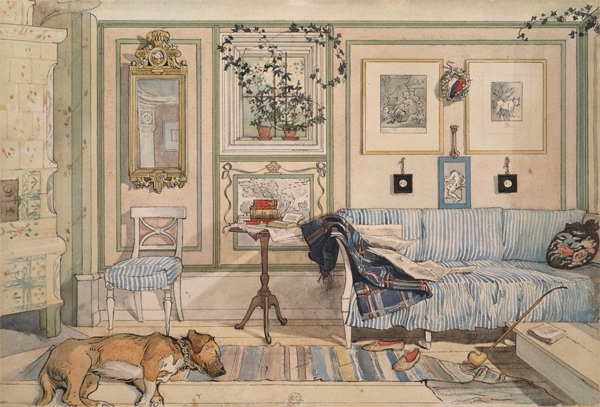

A Cosy Corner by Carl Larsson, 1894 via WikiPaintings

How does he do this? A room with rucked-up rugs, old newspapers, haphazard pipe and shoes, the chair and sofa covers sagging with use — and it’s an inviting, charming spot. Maybe the dog, oddly, humanizes it? Sunshine spilling in. But it’s the fond eye that captures the heart.

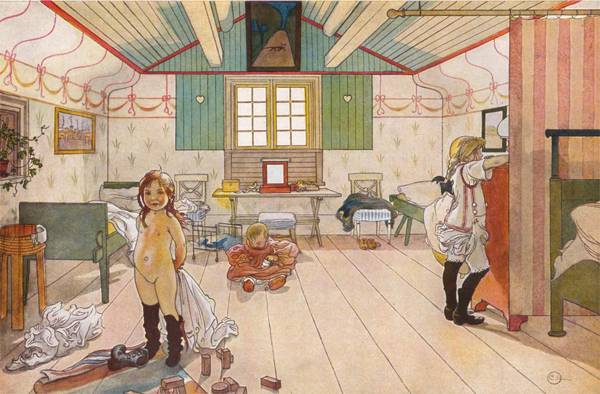

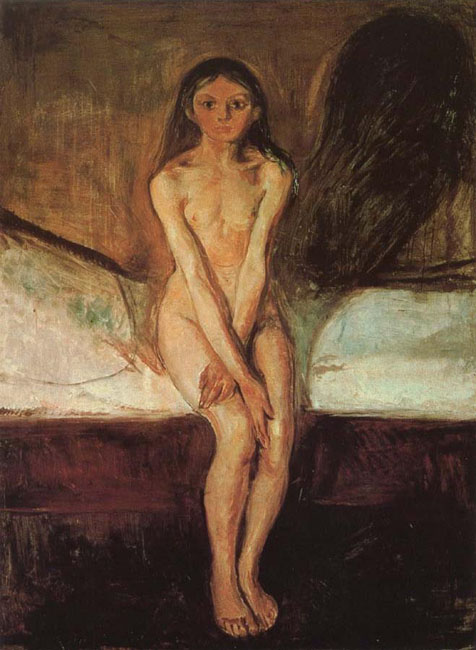

I don’t want to slip off into Freudo-Lulu-Land here but the contrast of Munch’s naked bodies and Larsson’s unclothed ones is instructive.

Puberty by Edvard Munch, 1894 via WikiPaintings

Mammas and the Little Girls Room by Carl Larsson, 1897 via WikiPaintings

The Model on the Table by Carl Larsson, 1906 via WikiPaintings

_____________________________________________________

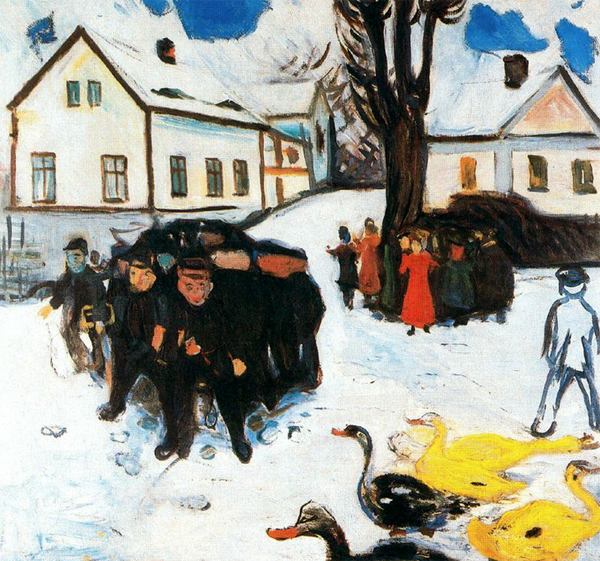

The Village Street by Edvard Munch, 1905-1906 via WikiPaintings

The Bridge by Carl Larsson, 1896 via WikiPaintings

There’s no question that Munch is the more daring painter, questing after more terrible truths with modernist zeal. His canvases yowl with emotions. His perspective often crazily telescopes, with rooms narrow and too deep or foregrounded roads that attenuate out to strenuous distances. His paintings are imperatives that want to meddle in your guts.

Larsson is a conventional painter with a familiar human perspective. He broke no new stylistic ground, grappled with garden-variety demons. But he documented a family’s life with fondness and a generous spirit — and I wonder why our sense of art today seems to bar this sensibility from the mix. Can we have canvases fronted not only with noisy nervous waterfowl but with a lovable lop-earred pig?

____________________________________________________________

look further:

Edvard Munch

- • Oslo’s Munch Museum — not as visually vital once you switch to English language

- • Edvard Munch organization

- • Amazon’s Edvard Munch page

- • Which includes The Private Journals of Edvard Munch: We Are Flames Which Pour Out of the Earth, a Kindle book that may be worth investigating,

Carl Larsson

- • Official homepage of the artist Carl Larsson — includes information on visiting the house which has been preserved.

- • Amazon’s Carl Larsson page — books in multi-languages.

- • There are also many notecards and calendars you can search for. Even a coloring book.