Artmaking

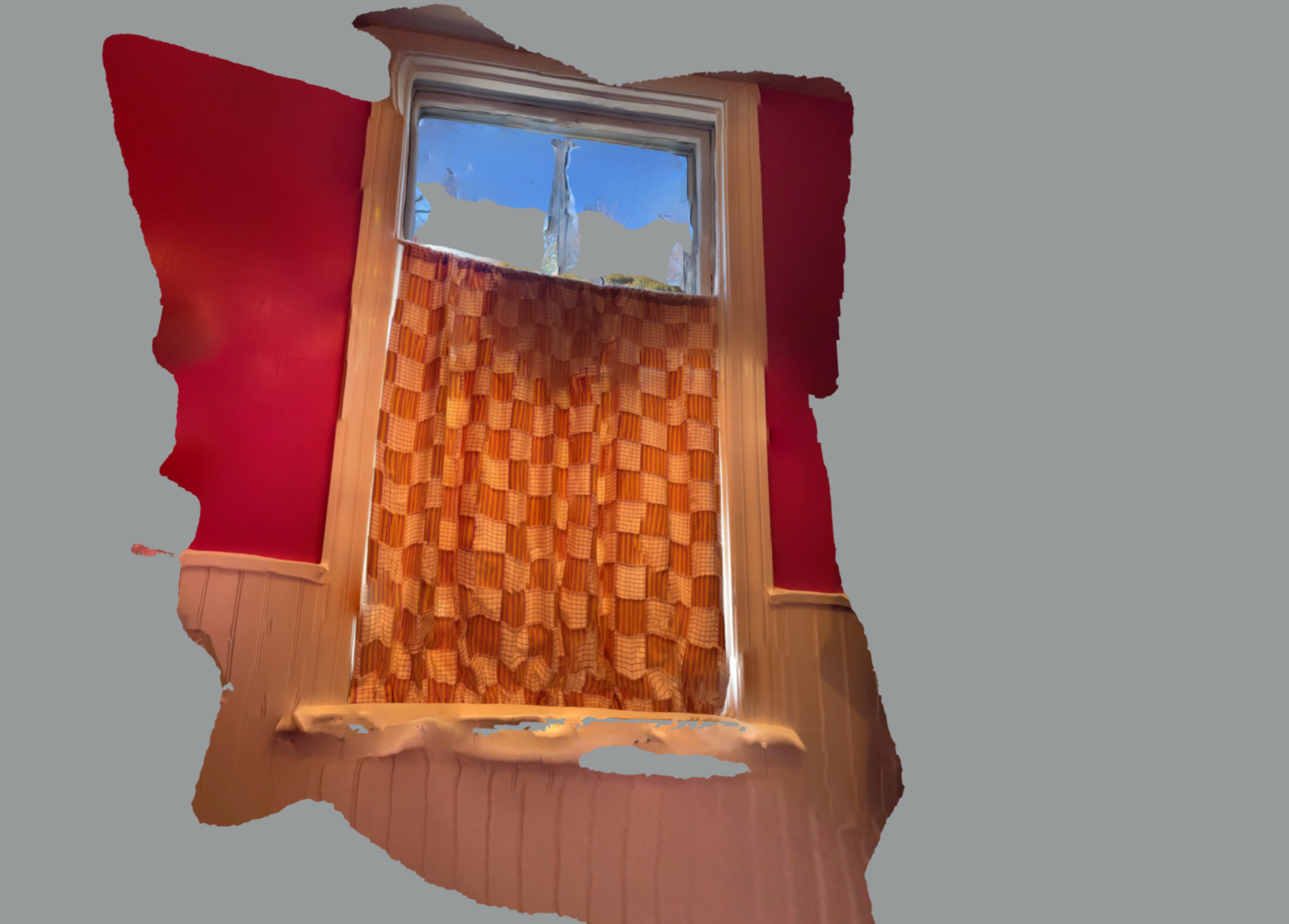

Learning to Be a LiDARer

Learning to Be a LiDARer Undoubtedly there is a cartoonish — or more politely said painterly — effect to LiDAR scans. Not …

LiDAR Lights Up My Life

LiDAR Lights Up My Life I’m full of juice! Don’t know if this is how other artists experience it but I’ve …

Inward with the Droste Spiral

Playground – Layered Shapes

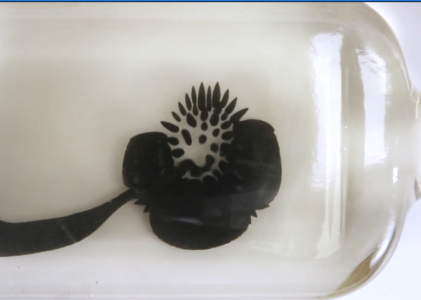

Calligraphy in Motion, a Follow-up

Calligraphy in Motion, a Follow-up A few days ago I wrote a post about Rus Khasanov whose videoed ABCs make you rethink what …

Cartoon Saloon Savvy

Cartoon Saloon Savvy Article by Mark O’Connell New Yorker, Story Time, Dec 21, 2020, p. 26 fl When the director of Pixar’s …

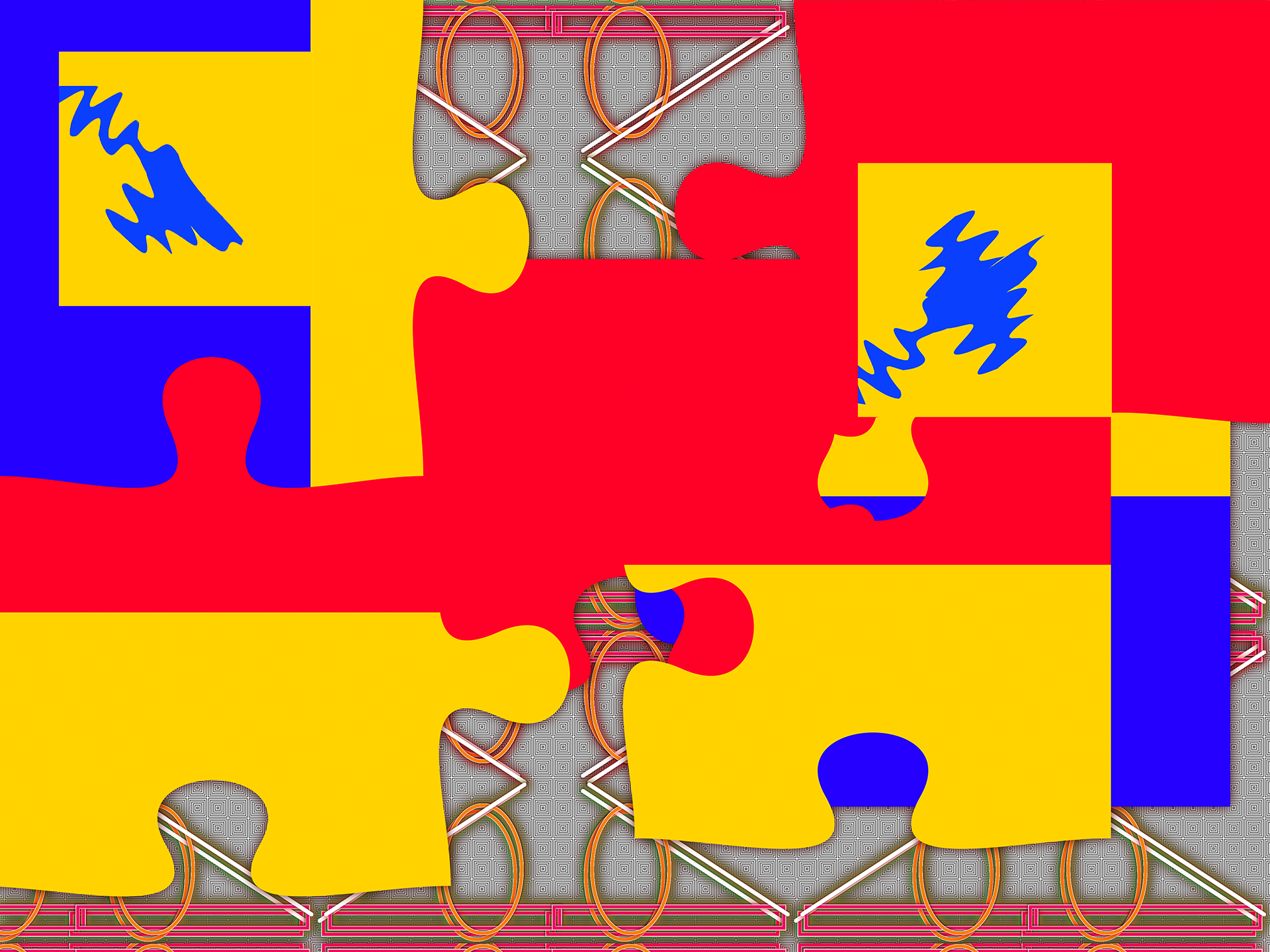

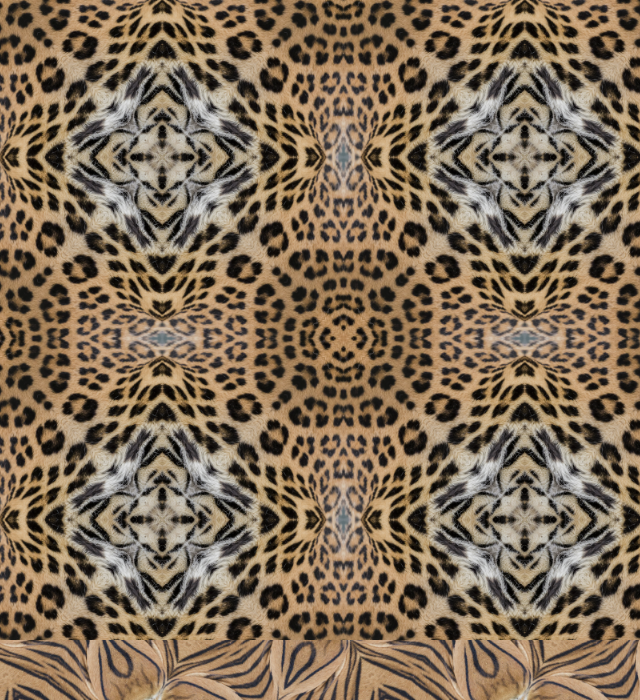

When More Is Better Yet

A. Two patterns in one frame. B. Pattern unit compiled from A, tiled out into a pattern. C. Same as B but with alpha (blank …

Tile Photos FX, puzzle-cut mode

To Signify: A Tincture of Pink

“Adults and children huddle around a brazier, or coal fire, to hear ghost stories.” “A man, perhaps the …

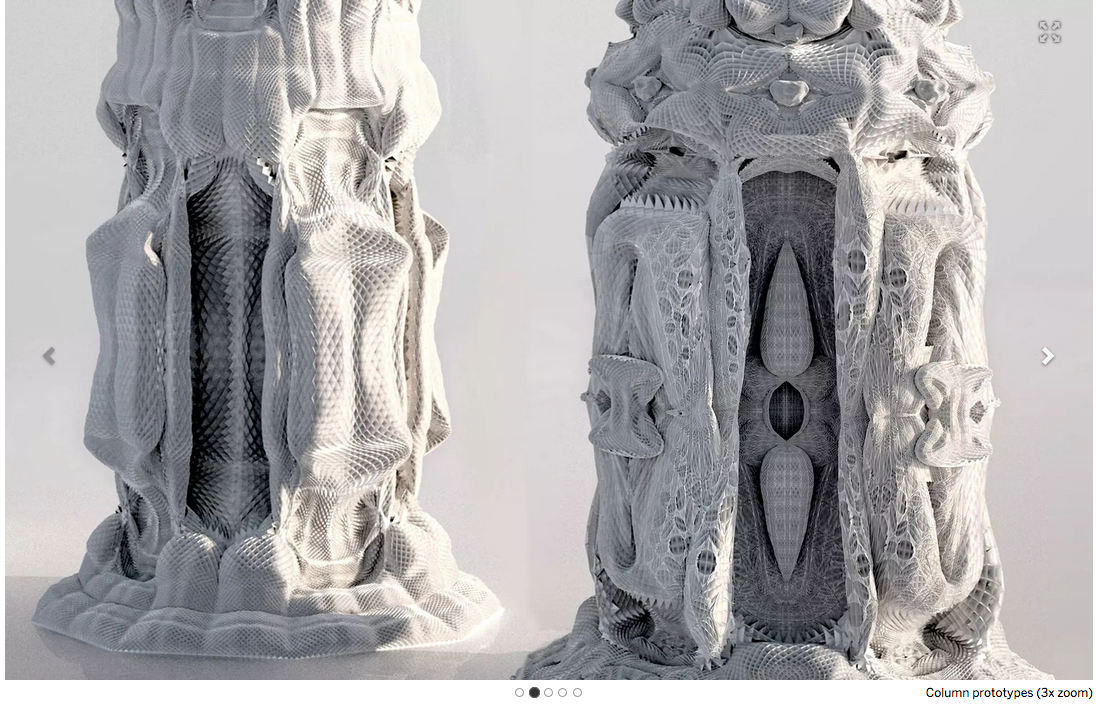

Michael Hansmeyer and the Fourth Industrial Revolution

Art of Tuesday, 022216

Once you see the ceramic hybrids of Gerard Ferrari, they may wander in the back of your mind for weeks. He promiscuously combines beastie …

Quick heads-up on free textures

CG Textures, an endless compendium of images, is just now processing a new batch of animal and bird photographs. Glorious! If you don’t already have …

Let the Gambol in the Goodies begin

In this launch of the Green as Sky blog I welcome you to all I find fascinating — and hope that you’ll find delight here …